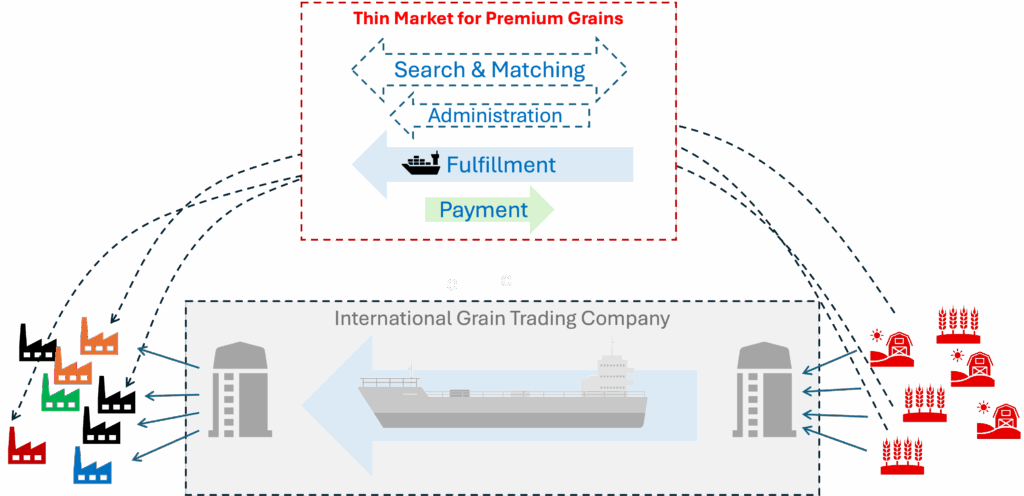

World grain trade is dominated by large international grain trading companies who orchestrate massive shipments of bulk grains. To pay for that, grain companies typically buy the grain outright from the producers and sell it on to the eventual buyers. The difference between price at the farm gate and final delivered price is the margin they use to fund their operations and profit.

From a thin/thick, perspective, they oversee thick markets at either end of the journey (Figure 1), while reserving the intervening steps to their internal operations. To make this work, they must maximize shipment size, since a bulk vessel can carry 10,000 to 60,000 metric tons at a time. With such large individual shipment volumes, they must manage their sailing schedule very carefully.

To be efficient, they need to consolidate many farm outputs for each individual type or grade of grain. At both ends, the trading companies have installed relatively thick market systems around a limited number of product types. Farmers can deliver their grain to an elevator at a railhead and be paid quickly for the weight of their delivered and graded crop. Overseas millers and distributors can buy large quantities from storage at a nearby port. It’s an efficient and sensible system as long as the trading companies don’t have to manage too much variety or offer special handling for smaller volumes. For that reason, it handles most of the volume in global grain trading.

The lost opportunity resides in the potential to trade smaller volumes of specialty, premium grains. There is ample evidence that end users like millers, bakers, pasta makers, breweries, etc. can find ways to use specialty grains to offer premium products, or save money on preduction with higher yielding ingredients.

Unfortunately, Figure 2 illustrates the challenge that has limited these opportunities on many (most?) overseas sales. Put simply, the market for overseas sales of premium grains is very thin. That makes it hard to achieve for a number of reasons:

- The sellers and buyers don’t know each other and there is no easy way for them to find one another.

- The parties must learn to handle the complexities of administering international shipments and administration that the bulk trading companies have reduced to a routine.

- The parties must arrange for transport that can handle smaller volumes. Fortunately, this aspect has become much easier with the burgeoning international intermodal container network.

- The parties must arrange the legal, insurance and payment details that the bulk trading companies hide them from.

Apart from the largely solved problem of actual shipping, all of these challenges are rooted in ond factor: the difficulty in learning, understanding and sharing information. What are the import restrictions at the destination country? What cleaning standards must be met before the shipping container is sealed and how must the shipper document and prove that? How does a farmer prove the quality of its crop to a buyer an ocean away? What sort of samples will be required before the deal is finalized and how must they be packed and documented? The list is long, detailed and sometimes obscure. It also varies depending on which country’s farm is selling which grain to which type of buyer in which other country.

The bottom line is that it will cost the two parties a lot of time and money to overcome all of these challenges. It is even worse if it has to be repeated for each shipment. If the shipment volume is relatively small and the quality price premium is modest, the parties likely won’t bother.

That is pretty much the definition of a market that is too thin to exist unless it has a lot of help.